The History of Brimscombe Mill

View of Brimscombe Mills from Brimscombe Lane showing the gables of Brimscombe Mill House courtesey of Howard Beard

The history of Brimscombe Mill written by local historian, Sharon Mansell, B.A. Oxon

As you walk around the bustling Social Enterprises in Brimscombe Mill today and witness the amazing renovation of this once derelict site, look into the vast roof above you and reflect on the many things that were once made here. Along with Brimscombe Port and the Thames and Severn canal, this Mill was part of England’s first Industrial Revolution.

Most of the buildings that were erected have long gone and their history is hard to trace. Even with the existing buildings, it is hard to decipher what they were once used for. For some of the time, Brimscombe Mill was divided into Upper Mill and Lower Mill but often it was worked as one site. This confusion along with the dearth of details for some decades has made it difficult to write its history. However, what is clear is that the area has seen many changes. Over the course of five hundred years, it went from rural tranquillity to becoming a centre of local industry which in turn fell into decay and dereliction during the course of the twentieth century. It is now rising like a phoenix to showcase how Social Enterprises can change the way we do business and the economy.

Where can we start from? The Domesday Book 1086

We can catch glimpses of Brimscombe Mill as far back as the Early Medieval Period. The use of water to power machinery has been known from very early times and this was one of the chief reasons for the settlement of Brimscombe and spread of population in the Stroud Valleys. We don’t know when the local inhabitants began to use water power but The Domesday Book of 1086 records 5 mills in the parish of Bisley and 8 in Minchinhampton. Brimscombe stood in both these parishes with the river Frome marking the parish boundaries and how fanciful is it to think that the Normans saw one of these mills on this site? These early mills were used for corn but by the early 14th century fulling mills were operating locally, one being at Brimscombe. There are reasons to conclude that this was on the site of Brimscombe Mill standing as it did near an ancient highway running across the valley and linking with east-west roads on both sides of the hill, now recognisable as tracks and lanes but formerly the main thoroughfares in the district. Being on the river it was in an ideal position to have a mill. It must be remembered that the Thames and Severn Canal was not opened until 1789 and the Stroud to Cirencester Road was not built until 1815.

Did Dick Whittington own Brimscombe Mill?

So, the early history of Brimscombe Mill is linked to using the river Frome to grind corn and then take part in the cloth industry. To fully understand this history requires a little knowledge of the production of cloth. Throughout the Middle Ages huge flocks of sheep were kept on the Cotswolds, and the wool industry became very important for the local economy. The most famous Cotswold merchant of all was “Dick” Whittington (1358-1423) who was born at Pauntley, south of Ledbury, and made his fortune by exporting the finest cloths. He was three times Lord Mayor of London and in 1395 he acquired a large part of Stroud and the valley up to Brimscombe. Perhaps it was through him that the Stroud cloths first gained their high reputation on the continent. Did Dick Whittington own Brimscombe Mill?

The first fulling mill

Fulling was when woollen cloth was cleansed and thickened, it was the first part of the cloth making process to be mechanised, moving to sites with a good supply of running water from the 12th century. It was first carried out by men walking on it, but water powered stocks were developed which repeatedly pounded the cloth causing it to felt and shrink. There is a good model of the fulling stocks in Stroud Museum in the Park. The remnants of a Fourteenth Century fulling mill have been detected in the garden of Brimscombe House. It was probably quite small, probably housing only one water wheel.

The earliest specific reference to Brimscombe Mill is in 1539 when John Bigg was leased 2 fulling mills at Brimscombe. He lived in the old Mill House at Brimcombe Mill known as Biggs Place, also known as Brimscombe House and later Dalloways. This house is now demolished.

The expansion of the fulling mill

By 1594 Ursula Bigge was married to Thomas Bigge of Stroud and she owned the mills and Bigges Place. (note that spellings in this period could be rather slapdash!). Throughout the next century documentary evidence shows how successive owners developed Brimscombe Mill, bringing more of the cloth making processes onto the same site. For centuries these processes had taken place in the cottages built along the sides of the Stroud Valley but now clothiers sought to build bigger and more complex mills so that everything could be overseen and regulated. In 1648 Henry Fowler of Minchinhampton sold Brimscombe House together with a fulling mill, gig mill, corn mill and three gardens and Over Rack Close to William Webb of Stroud, a clothier. Brimscombe House, also known as Biggs Place and Dalloways, remained on this site, adapted and added to over the centuries until it was brutally demolished in 1956. One of the existing photos shows it located by the river with the low building that now houses the Sanctuary directly behind it.

Brimscombe House, West Wing 1956 by Lionel Walrond digitised by Dr Ray Wilson licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0

By 1729 the Brimscombe fulling mill had been acquired by Samuel Peach and insured for £300. By 1733 the site had grown. In 1733 Brice Seed and Water Davis conveyed “all that fulling mill consisting of three stocks and a gig mill ……… and the new erected building standing near to the mill pond designed for a grist mill (a mill that grinds grain into flour) but now converted into a messuage (a dwelling house with outbuildings and land assigned to its use) or tenement” to John Dallaway who occupied the premises at the time. Notice also the first mention of the mill pond which is presumably the mill pond that we see today. We can see the gradual transformation of the fulling mill into an integrated mill.

The beginnings of The Industrial Revolution 1750-1790

With the appearance of the Dallaway family, Brimscombe Mill entered into its heyday as a centre for textile production. Its history mirrors the history of the Stroud Valleys as cloth production moved to the fast-flowing rivers and mills grew up at a phenomenal pace. Between 1750 and 1820 more than 180 sites in the Stroud District were used as woollen mills and Brimscombe Mill was initially one of the more successful ones. There was a huge concentration of mills along the Frome with most upstream from Stroud where the gradient of the valley was steepest. John Dallaway was a far-sighted man, supporting the idea of a canal to improve communications to and from his mill. He produced a pamphlet in 1753 where he suggested a canal between the Thames and Severn linking Stroud to the Thames and the port of Bristol. In 1785 William Dallaway, grandson of the above, sold a piece of land to the Thames and Severn Canal Company, the land was alongside the edge of his property.

John Dallaway had 13 children, the eldest William was married at 39 to Elizabeth Hopton and their marriage settlement in 1760 includes:

the growing Brimscombe Mill site, the fulling and gig mills, and “also all those buildings called the knapping mill house” with the rack hill.

Not included in the settlement were Bigges Place and half the new building which was situated at the lower part of the mill court and comprised the scouring dyehouse and the blue dyehouse. The mention of dyes is interesting and shows how enterprising the Dallaways were as it was usual to send cloth to specialised dyers, especially blue as it was the most difficult colour to use.

Families like the Dallaways made considerable fortunes, built handsome houses and played a leading role in the life of the areas as seen by the appointment of William Dallaway as sheriff of the county in 1776. However, the cloth trade was a precarious industry and by his death in 1787, James the heir and younger brother had lost everything and been declared bankrupt. Their name lived on in the Tudor house that was eventually demolished on the Brimscombe Mill site and today in the Dallaway road off Brewery Lane in Thrupp.

In 1779 The New History of Gloucestershire describes Brimscombe thus:

Brimscomb Is a little hamlet in the Lower Lypiat division, situated in a pleasant valley, on the banks of the Froom, surrounded with woods, and lies in the common road between Minchin Hampton and Stroud. There is in this place an ancient house, formerly called Bigge’s Place, with clothing-mills adjoining, which was the property of the late William Dallaway, esq; who served the office of high sheriff of this county in the year 1776 and carried on a large trade in the clothing business ‘till the time of his death.

In 1790 Brimscombe Mill was sold to John Lewis, it included:

Bigges Place (later called variously Dallaways and Brimscombe Mill House), the range of buildings lately erected by William and James, the fulling and gig mill, the knapping mill, the scarlet, blue and scouring dyehouses, the shear shops and buildings called the wood house, warehouse and coal ash house.

The Industrial Revolution- Brimscombe Mill 1790-1850

The Lewis family who took over in 1790 managed to restore the fortunes of the site. The period until 1820 was a time of growth in the textile industry. In 1804 we read of coals being delivered to Mr Joseph Lewis who refused to pay the correct tonnage charge, keen to maximise profit or simply trying to survive?

Joseph Lewis left the mill to his wife Mary, to be divided after her death among their four children, John, William, George and Elizabeth. The three brothers carried on cloth making and dyeing at Brimscombe Mill until 1827 when George sold out to the other two. They carried on until John’s death in 1838. Steam engines had been installed by 1833.

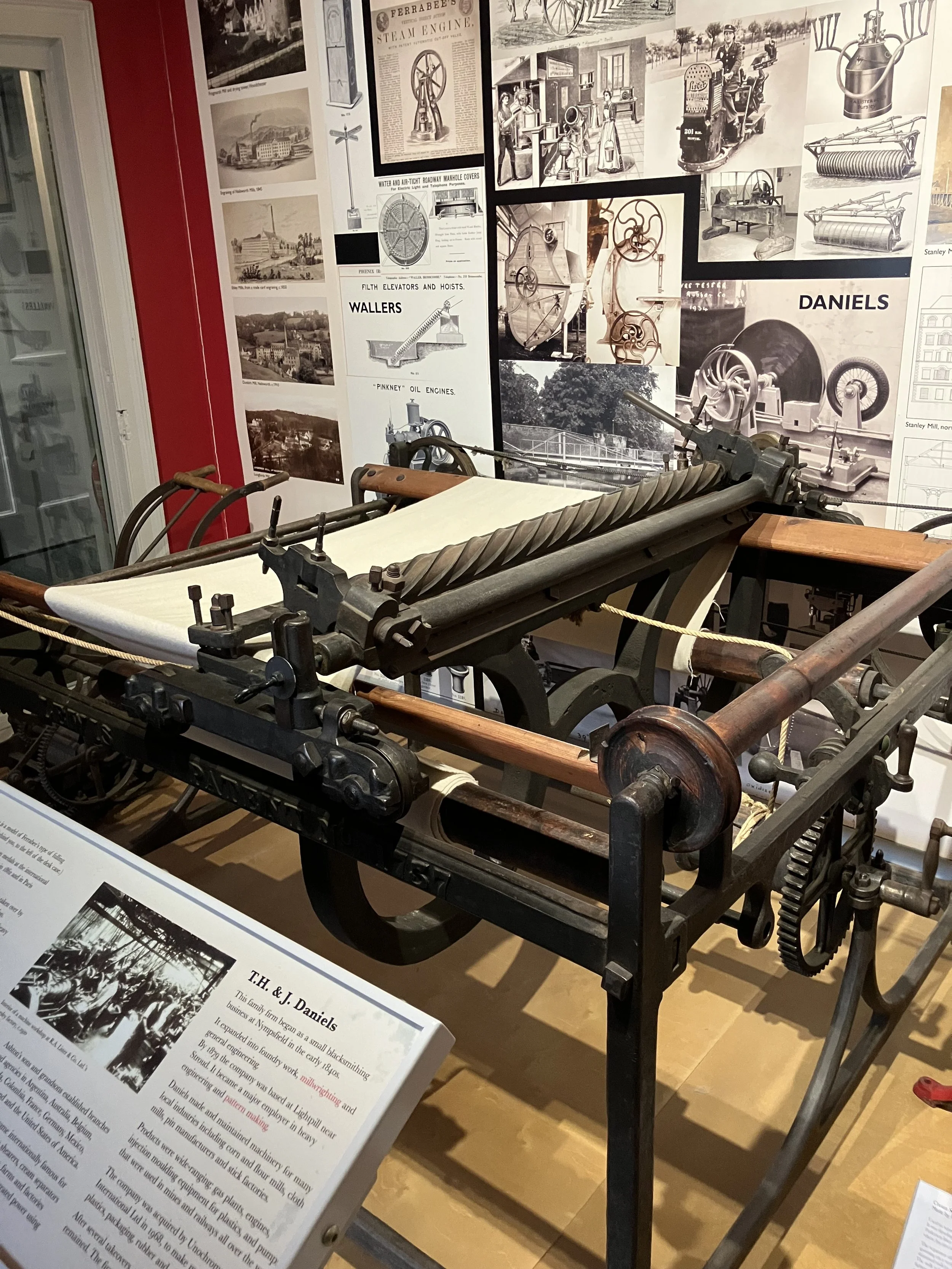

The Rotary Shearing Machine 1815 - Patent number 1757- The beginning of Stroud’s famous lawnmower at Brimscombe Mill

We get a glimpse of the entrepreneurial nature of the cloth industry with the invention of the rotary shearing machine. In Stroud Museum in the Park, you can see the machine that John Lewis, owner of Brimscombe Mill, patented in 1815. Both he and Stephen Price of Dudbridge had been designing and building new machines but Lewis patented his 2 months before his rival. Until then the rough surface of the cloth, known as the nap, had been cut by skilled men using huge scissor-like shears. The new machine could do their job much more quickly and evenly. Lewis claimed that by 1829 he had already sold thousands of his new machine. As you visit the Bike Drop, stop for a minute and ponder on the fact that a significant textile invention was invented near to where you are standing!

Edwin Beard Budding who invented the world’s first mechanical lawnmower in 1830 got his idea from coming into contact with the rotary shearing machine. He had worked as a mechanic in various textile mills in the Stroud area and presumably watched the Rotary Shearing Machine in action.

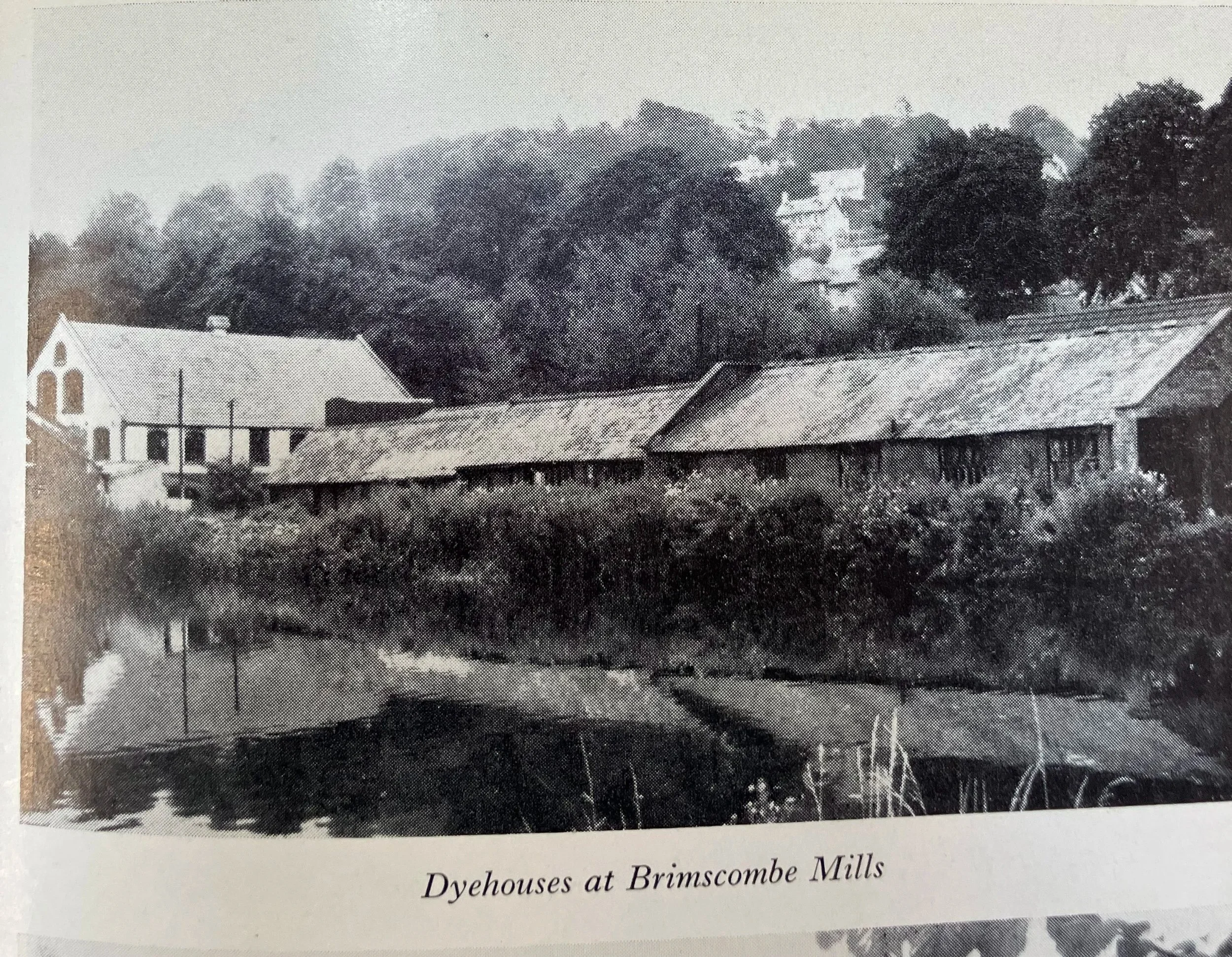

Dyehouses at Brimscombe Mills with thanks to Jennifer Tann in "Gloucestershire Woollen Mills”.

Rotary Shearing Machine designed by John Lewis in 1815. On show in Stroud Museum in the Park. Reference STGCML.65.

The Lewis family was typical of the more successful cloth manufacturers of the area as they built bigger and more complex mills, trying to carry out many of the cloth making operations on the same site. 1795-1815 were the years of lucrative army and navy contracts, culminating in the battle of Waterloo. Stroud was famous for producing cloth for military uniforms. The site reflects the history of cloth making in the Stroud area, with the industry waxing and waning over the years. Between 1800 and 1825 there was another period of prosperity and a great rebuilding of textile sites.

Brimscombe Mill was in a perfect position to take advantage of the growth of the textile industry as it could take advantage of improved communications. Before the construction of the turnpike road from Stroud to Cirencester in 1815, now the A419, it had taken a horse and cart all day to travel from Stroud to Chalford and back again via the lanes that traversed the hills and valleys, Thrupp Lane being the main thoroughfare between Stroud and Chalford. With the opening of the Thames and Severn canal in 1789 and the building of Brimscombe Port, access to the Severn and London was possible and then of course the opening of the railway in 1845 further improved communications.

As in other areas Brimscombe Mill continued to be important even when steam power gradually replaced water power as by now it was a well-established manufacturing site with an available workforce and space to expand. However, little did the owners realise that the industry was to enter into a period of inevitable decline. Their thick, heavily felted cloth was no longer an essential part of a gentleman’s wardrobe. Finer stuff became more fashionable and these manufacturers were slow to adapt.

By 1845 in the sale particulars for Brimscombe Mill, we get an idea of how the site had grown, particularly with a mention of the 2 steam engines. Brimscombe Mill is typical of the factories of the time, using steam power to supplement water power rather than supplant it. Also 2 mills are mentioned, giving us the idea that Upper and Lower Mills were now distinct industrial areas:

Upper Mill- (Used for wool and yarn preparation and dyeing.) Ground floor- cloth washers, iron stocks, wheels, shafts and gears for driving stocks, either by water wheel or steam engine, 1 gig mill

First floor- Cutting shop

Second floor- 2 engine shops

Third Floor- Engine shop

Fourth Floor- Mule shop, Engine shop, 40hp steam engine

Wool Dyehouse

Vat House with 12 dyeing vats with covers and steam pipes to each, 1 copper furnace

Cloth dyehouse

Wool scouring and washing houses

Handle Setting Shop, Wool and Cloth Store.

Mill Yard: Cast -iron cistern for steaming cloth

Rack Hill: 4 oak cloth racks

There was also a bridge for landing coal from the canal and pipes for conveying water from the reservoir near the road, under the pond to the dyehouse.

Lower Mill- (used for weaving) Three water wheels, gear for driving stocks and gig mill, 6 pairs of iron stocks, 1 pair of cloth perches, 6 gig mills, double cloth washer, 20hp steam engine etc

From the above details we can deduce that the whole site was a hive of industrial activity with many stages of cloth production taking place. If you compare an 1884 map of the area with one published in 1971, you can get a rough idea of how the building layout has changed over the years. Photos from the beginning of the 20th century show that Lower and Upper Mills both had a large factory complete with a very tall chimney, both now gone.

The decline of the cloth industry

Another depression in the cloth industry followed in the 1830s. Due to over production, competition from the north of England and changing fashions. There was another decline from 1870s. This was partly caused by the governments adherence to a policy of free trade in the face of growing economies elsewhere. The new machinery, the all-important spinning mules and power looms came to be supplied by Yorkshire and Lancashire firms. The mills in the north of England had an easier access to coal, vital for the steam engines. High tariffs in selected European countries and the USA made it impossible for high-cost West of England cloths to compete. By adhering to the top of the range in quality and price, besides a reluctance to adopt new yarns or explore new products, Gloucestershire woollen manufacturers showed insufficient vision for the future. On William’s death in 1843, his creditors secured a court order for the sale of the property to meet their claims. It then, as seen above, included Upper and Lower Mills.

The mills were sold to John Ferrabee who had established the Phoenix Iron Works Foundry at Thrupp Mill in 1828, making cloth-making machinery, farm machinery and steam engines. Then John Webb was said to be occupying the mills while Christopher Smith was occupying the dyeing premises. In 1845 the mills were again for sale and bought by Samuel Stephens Marling who leased it to Thomas William and Thomas Coke White for 21 years for £450.

The paternalism of the factory owners

The Victorian mill owners were keen to be seen as paternalistic and philanthropic to the locality and the Evans family, who leased Brimscombe Mill in 1858, were no exception. Their purposes in doing so were undoubtedly mixed; they were concerned to look after their workers but were also anxious to establish their social standing in their communities in relation to the landed classes who traditionally dominated the social scene.

In Brimscombe, the Brimscombe Mission chapel was erected in the 1870s by Mrs Evans, wife of the owner and formally opened in 1882. This denomination had previously met in Bourne Mills but as it grew in numbers, Mr Evans came forward and allowed the use of his wool warehouse. Then he erected a more suitable room in his mill yard. Eventually the congregation became too large and Mr Evans agreed to pay for a new building on a piece of land formerly known as “the Rack Hill”, close to the Silk Mill also owned by Mr Evans, now Gordon Terrace.

The chapel is now Peter Joy Estate Agency.

Many of the millowners were interested in providing some education to their workers and perhaps a Sunday school took place in the mission chapel.

Edward Holt Evans started evening classes in 1889 so that young men in Brimscombe could further their education. This was the start of Brimscombe Polytechnic in which the Evans family always took a keen interest.

The Polytechnic was set up in the Thames and Severn Headquarters in Brimscombe Port. It also occupied part of Brimscombe Lower Mills, nearest the main road as seen in a photo c. 1906/7. This was only a temporary measure while the headquarters was renovated for use as a school. The Brimscombe Craft School opened on September 3rd 1906 for boys of the age of 12, selected from neighbouring Elementary Schools. By 1911 the Poly taught practical skills like metalwork and woodwork. There is a photo from the 1930s showing pupils being taught to swim in the canal!

At the turn of the century Brimscombe had its own Fire Brigade and the horse drawn engine was housed at Brimscombe Mill. The engine was manned by employees and was the private property of the firm. Owing to the ageing personnel they were looked upon as a joke and it was disbanded when the National Fire Service was inaugurated. After the virtual disuse of their Brimscombe property from 1920, Marling and Evans Ltd transported about a dozen employees to Stanley Mills daily in their light truck with seats to accommodate passengers. This only continued for a short time.

Brimscombe Polytechnic once occupied the part of Lower Mills nearest the road. 1906/7 Courtesy of Howard Beard.

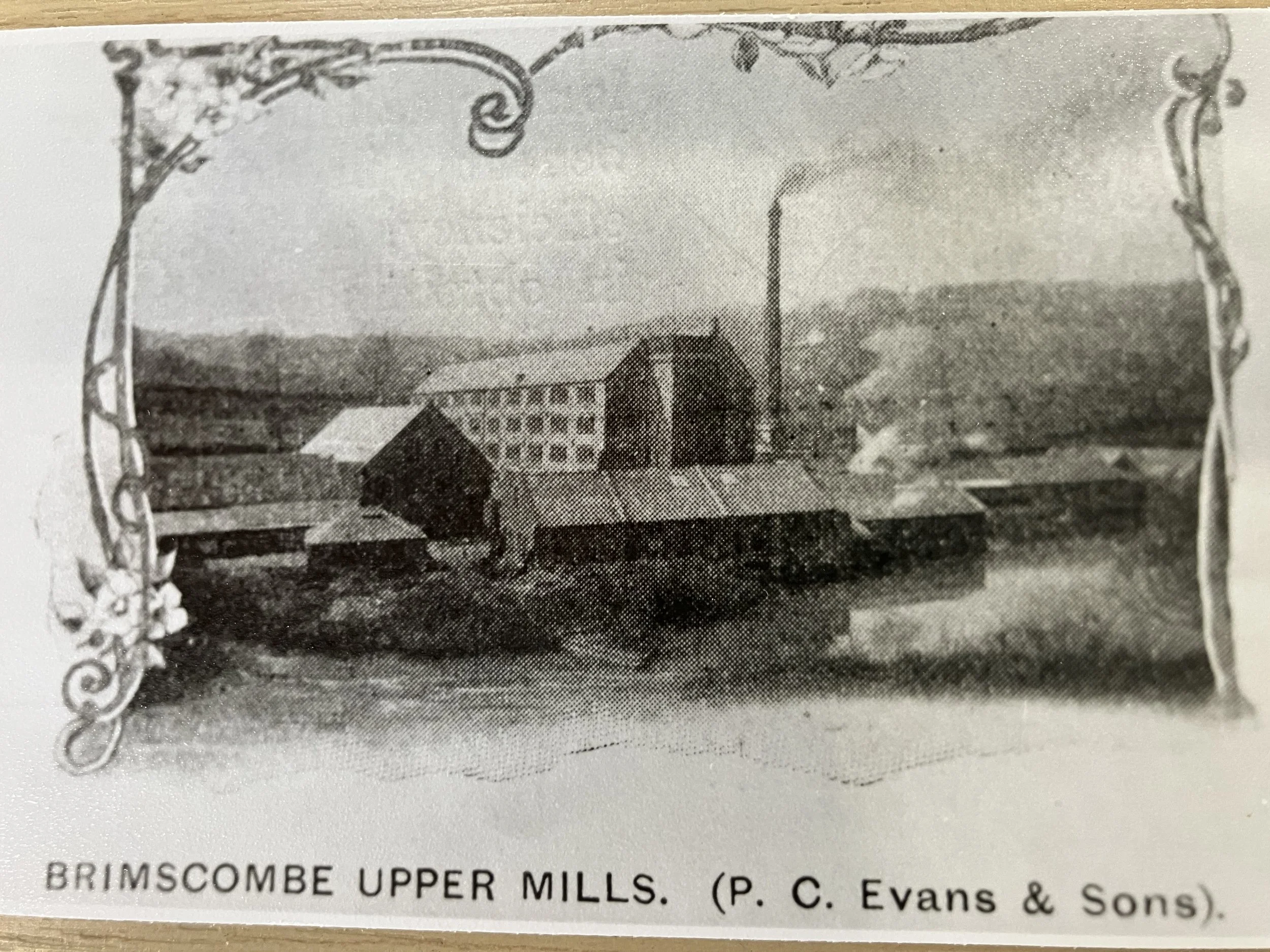

A return to prosperity under P.C. Evans

In 1858 Marling leased Brimscombe Upper and Lower Mills to P.C. Evans and John William Bishop, clothiers and so began the last period of prosperity for the production of cloth at Brimscombe Mills. The previous tenants had failed, yet again another example of the boom and bust of the cloth industry. Evans was the son of Aaron Evans who had worked one of the mills in the Toadsmoor Valley. The schedule which follows on the deed shows that the uses of the various floors probably remained much the same. Marling had erected a new loom shed (Was this the single storey weaving shed, our main building today, with its characteristic north light roof which avoided direct sunlight, casting an even light on the looms?) and a building which was to be an oiling house and mechanic’s shop. He agreed to erect a building at the Lower Mill where Evans could install his dyeing machinery. Within a few years both mills were run by P.C. Evans.

Brimscombe Upper Mills C. 1900-1910. Unloading coal into the Mills courtesy of Howard Beard.

Brimscombe Upper Mills 1904 Courtesy of Gloucester Archives D9746/2/23/20

By 1889 P.C. Evans had 120 looms and 6,400 spindles at the 2 mills. 2 years later the looms had been increased to 144. He seems to have been more adventurous than other millowners and tried to branch out into new fabrics. He had the first worsted spinning plant in Gloucestershire. As well as the usual broadcloths, he made a remarkable variety of cloths including worsteds, tweeds and serges in light weights for warmer climates and Bedford cord and waterproofs so that he was not dependant on one market. He had agencies in Vienna, New Zealand, Australia and the USA. When he died, he left 4 sons in the business and by 1914 the fifth generation of his family was working there. The success of this company at a time when so many other millowners were failing shows the importance of enterprising management and a succession of sons devoted to the business. P.C. Evans was prepared to invest more capital while trying to maintain a firm financial footing.

By 1900 the cloth industry in the West was in a serious decline. Only 19 mills in Gloucester still made cloth. In 2000 there was only one cloth making mill in the Stroud District. The county had been slow in recognising the importance of technical education. Evans seemed to have been better at surviving and didn’t lack the capital to make fresh investments in his company. However, even this company could see that the writing was on the wall for the cloth industry in this area. Already in 1907, the company was selling off much of their machinery. As seen in their sales brochure:

BRIMSCOMBE & PORT MILLS BRIMSCOMBE

CATALOGUE OF THE SURPLUS WOOLLEN & WORSTED MACHINERY

EDDISON, TAYLOR & BOOTH HAVE RECEIVED INSTRUCTIONS FROM MESSRS P.C. EVANS, WHO ARE CONCENTRATING THEIR MACHINERY, TO SELL BY AUCTION. Ref note. 1

There were 7 pages of textile machinery and sundries of the cloth industry put up for sale.

In 1920 the firm amalgamated with Marling and Co Ltd at Stanley and Ebley Mills. Little cloth production was undertaken here after this and the mills were eventually sold.

In many ways the history of Brimscombe Mill is the history of the Stroud area, the rise and fall of the textile industry. The old textile buildings either had to adapt to other industries or they fell into permanent decay. Most of the textile buildings on this site collapsed or were deliberately destroyed.

The large Lower Mill factory was mostly destroyed by fire in 1920 and the Upper Mill factory was demolished in 1948. The latter stood where the large car parking area is now.

Brimscombe Mill after 1920

The Lower Mills

Brimscombe Mills lay unoccupied for a considerable time. When cloth making ceased a number of different businesses moved in, chiefly metalworking firms here. The Lower Mills now are the buildings to the side of the Mill pond behind the football club.

In the centre and southern part of Lower Mills, during WWI, rubber heels for shoes and rubber tyres were produced by the Metcalf brothers, trading as the Maroro Rubber Company. While the northern part was let as an iron foundry, where the Polytechnic occupied classrooms.

Brimscombe Lower Mill early 20th century Gloucester Archives D5483/20/8

Brimscombe Mill in the late 19th Century courtesy of Howard Beard

In 1920 the Gloucester Journal reported a huge fire at the rubber works.

BIG FIRE NEAR STROUD.

SEVERAL THOUSAND POUNDS DAMAGE. RUBBER WORKS PRACTICALLY DESTROYED.

An extensive trade was carried out at the works and a very considerable number of people will be thrown out of employment. Ref note.3

After the fire both firms continued to function in a much-reduced building until the Metcalf brothers moved back to the north of England and the former iron foundry owner went bankrupt.

By the mid-1920s car engineering and ironworks were taking place in this area. Precision Motor Machinery, founded in 1928 by F.T. Hammond of Chalford took premises at Lower Mills. The southern detached block of Lower Mills, containing water power, soon became the centre of much activity. The main line was reconditioning car and motor cycle engines. During WWII changes were made to the production of machine tool equipment for a large aircraft corporation, Alfred Herbert Ltd of Coventry. During the war the motor company was engaged in the production of equipment for firing machine guns for bomber or fighter aircraft, working with Parnall Aircraft Limited of Yate.

Being appointed direct contractors to the Admiralty, the years following the war saw many intricate components in special alloys produced. Much of their work was exhibited at Earls Court, Paris Salon and other Continental Motor Shows.

There was also a new owner for the iron foundry, J. Cousins. After the war, Sidney Charles Hole and his 2 partners Jack and Lawrence Lewis bought the premises next to Brimscombe football club from Jack Cousins a dapper gent who always sported a bow tie. They had both previously worked at Martyn’s ornamental ironworks in Cheltenham. By 1965 they had moved to Dudbridge until the firm closed in 1996 and made way for the Sainsbury store. A sales brochure for the sale of the Mills in 1961 shows part of the remains of Lower Mills as an Iron foundry.

The foundry was immediately taken over by Messrs Autocrafts who then moved from but a few yards from the dyehouse site of Brimscombe Mills where they had sustained a motor car body building and repairing establishment for some years.

From 1946 the Lower Mill site was also occupied by Kimberley and Hogg, electro-platers and metal polishers.

Brimscombe Upper and Lower Mills early 20th century Gloucester Archives D9746/2/23/19

The Upper Mills

This is the part of Brimscombe Mill that The Grace Network now occupy.

The managing director of Marling and Evans, Mr Gerald A. Evans became willing to let small portions of the Upper mill to various firms and thus the comprehensive premises were sold off piecemeal. A wood turning department of the Chalfont Stick company of St Marys’ Mills, Chalford was here for a few months followed by Kirby Heavens and Co breaking away from Critcheley Bros. of Brimscombe, who commenced a knitting needle business in the mechanics’ shop and drying store. This is where the Waterside Works premises next to the mill pond now are. They were well established by 1936. While Alexander and Angel of Cranham, poultry rearers, took the main mill and filled the many floors with battery reared chicks, which were then killed and packed for the London hotels, presumably sent up by rail.

After the firm returned to Cranham, R.K. Dundas occupied the premises during WWII becoming a shadow factory for Supermarine Ltd. A shadow factory was not intended to mean secrecy but rather the protected environment they would receive by being staffed by skilled motor industry workers, alongside their civilian motor industries. A document, from 1943, shows that R. K. Dundas had made considerable improvements to the site as they sought to challenge their rent with Marling and Evans. They had leased part of Upper Mill in 1940. As they quibbled over their rent for the site, a letter from the estate agents in 1943 said,

“As you are aware a portion of the premises is in a completely dilapidated condition and absolutely unfit for occupation. We may add that in normal times it would be extremely difficult to find a tenant at all.” Ref note.2

In 1945 Brimscombe Mill was offered for sale at auction. A plan drawn up for the sale shows the site occupied by the British Legion, Marling and Evans and the majority of it occupied by the Admiralty. Presumably this was describing the work carried out by R.K. Dundas? The premises were fire watched by men from the local factories and later by a rota of village men during WWII, showing their importance to the war effort.

At the same time Biggs Place, the Tudor house also known as Brimscombe House and Dalloways had been purchased and let out as flats.

In 1943 B.H.W. King who had an upholstering business at Chalford purchased part of Brimscombe Mills and began to make domestic appliances. He had no capital and lurched from one financial crisis to another. He let part of the Mills, the old spinning shop nearest the Ship Inn, to J.H. Kimberley and J. Hogg who readily obtained contracts for polishing and plating motor car and other components. King was eventually forced to sell up and Kimberley and Hogg leased a portion of Lower Mills.

The sales brochure of 1945 describes:

The Buildings- The main part of the factory are single storey and north lighted, and easily adaptable to almost any industry. The old derelict multi- storey Mill is not without value as a potential source of large quantities of building materials and as such is worthy of consideration in view of present shortages and difficulty in obtaining licences for such materials. Ref note.4

The main block of Brimscombe Mill was demolished in 1948. This stood where our car park is now.

A further sale in 1952 shows that more buildings have been demolished. The brochures for both sales show that the site had a vast range of buildings, many of which have been subsequently demolished. The 1952 describes:

Brimscombe Mills

Comprising

Main factory, well-appointed offices, canteen, stores and self-contained flat

Mains electricity, water, gas, and central heating.

Ref note.5

1952 Sales Brochure image. Ref note.5

In 1952 Messrs Lintafelt of High Wycombe bought Upper Mills and began to produce felt. For a while they employed King and some of his staff. They then sold to Greaves and Thomas, furniture makers who were here for a short time. Labour troubles ensued after 2 or 3 years and they closed at the end of March 1960. By 1961 it was up for sale again. After being empty for 4 years Messrs Orcene, Engineering and Industrial Chemists, took over, they were a subsidiary of Perolin Company, Manufacturing Chemist and had moved to Stroud from Warwickshire. In 1971 they employed 30 people and a document from 1989 shows that they made chemicals for use in public water supplies and swimming pools.

By this time the pond weirs, water wheels and mills had disappeared. Only some 19th century brick buildings remained. The fashion at the time was to demolish the old buildings if no immediate use could be found for them. This also happened in the Brimscombe port area where many of the old port buildings were bulldozed and pushed into the port which was then concreted over. Perolin demolished the Tudor house perhaps for a factory extension or some said it was for part of the road widening that took place. Alas, Dallaways, possibly the oldest building in the village, a fine Tudor building as seen in the existing photos, that had begun life as Bigges Place was ruthlessly destroyed on the pretext that squatters had moved in and it had been allowed to decay.

Little is currently known about what took place in Brimscombe Mills after the departure of the chemical companies. The Olympic Varnish Company occupied the Mills at the turn of the century. Owned by Bill and Ben Petyan, the company manufactured paper and paperboard packaging, The company also had other sites in Brimscombe so it is difficult to know what took place on each site.

1973 Brimscombe Mill by C.H.A Townley, digitised by Dr Ray Wilson Coaley.net

Brimscombe Mill 1999 Hugh Conway - Jones Collection. glosdocs.org.uk

Brimscombe Mill 1994. Hugh Conway-Jones Collection. glosdocs.org.uk

Maps of how the site has changed over the years

The below historical Ordinance Survey maps show how the site has changed through the centuries and give a visual representation of the wax and wane of the buildings on site.

Brimscombe Mill in the 21st Century

The geography of the area changed as the textile industry disappeared and other industries appeared. The Nineteenth Century mills were either knocked down or suffered extensively from fires. The Thames and Severn Canal struggled to compete with the railways and was eventually closed in 1933. The canal by the Mills dried up and was filled in. Today the service road between Brimscombe Mill and the Canal bookshop marks out the route of the canal. The hump backed bridge over the canal was removed because it was impractical for loaded double decker buses.

By the turn of the century most of the site of Brimscombe Mill was in a serious state of decay. A video on YouTube shows the woeful state of decay that existed here. Squatters and vandals had done much superficial damage and the paths and roads were covered with vegetation. Some small industries existed in some of the old buildings, for example Brimscombe Platers and Peritect Perimeter Protection in Lower Mill but the main buildings were empty. Other buildings were and still are occupied at Orchard Works and Waterside Works. Lorfords Contemporary occupy Orchard Works and a number of carpenters occupy Waterside Works.

In 2021 The Grace Network moved into the buildings left in The Upper Mills and began to transform this near derelict site and are continuing in this work today.

Brimscombe Mill has been occupied for over 500 years and possibly even longer. Sometimes run as one mill and sometimes divided into Upper and Lower Mill, its history mirrors that of other valleys in the Stroud area. Beginning life as a place of textile manufacture, its fortunes ebbed and flowed with the growth of the cloth industry. As this declined, at the end of the nineteenth century, Brimscombe Mill was adapted to accommodate a number of other industries. Buildings were added to, knocked down and abandoned as firms came and went. This is why it is so difficult to work out from existing maps what took place where and what the current buildings were used for.

By the year 2000 much of the site was derelict and in a sorry state. However, thanks to The Grace Network, it is now entering a new period of prosperity and change. Social Enterprises are growing here and breathing new life into the buildings. Derelict rooms and open spaces are being transformed. A revolution is quietly taking place which will transform the way we do business, the way we eat and the way we behave as a society.

Sharon Mansell B.A. Oxon

Reference notes

Ref note.1 - 1907 sales brochure courtesy of Stroud Museum in The Park- 1963 170/12

Ref note.2 - Quote from estate agent 1943 courtesy of Gloucester Archives- D1405/4/63

Ref note.3 - Fire of 1920 courtesy of Gloucester Archives D5483/20/8

Ref note.4 - Sales brochure of 1945 courtesy of Gloucester Archives- D1405/4/63

Ref note.5 - Sales brochure of 1952 courtesy of Gloucester Archives- D5483/20/8